A Trip Through Early Cinema's "Kingdom of Shadows"

The Cinema and Poetry of German Expressionism, & the Poetry of Its Cinema: Early European Horror Films

France and Germany dominated early movie horror. Italy and Denmark weren’t far behind. The U.S. managed to stay in the running—barely—with J. Searle Dawley and Thomas Edison’s 1910 Frankenstein one-reeler, and the dynamic duo of Tod Browning and Lon Chaney nearly single-handedly kept movie horror alive in the U.S. throughout the 1920s. (With a little unexpected help from D.W. Griffith.)

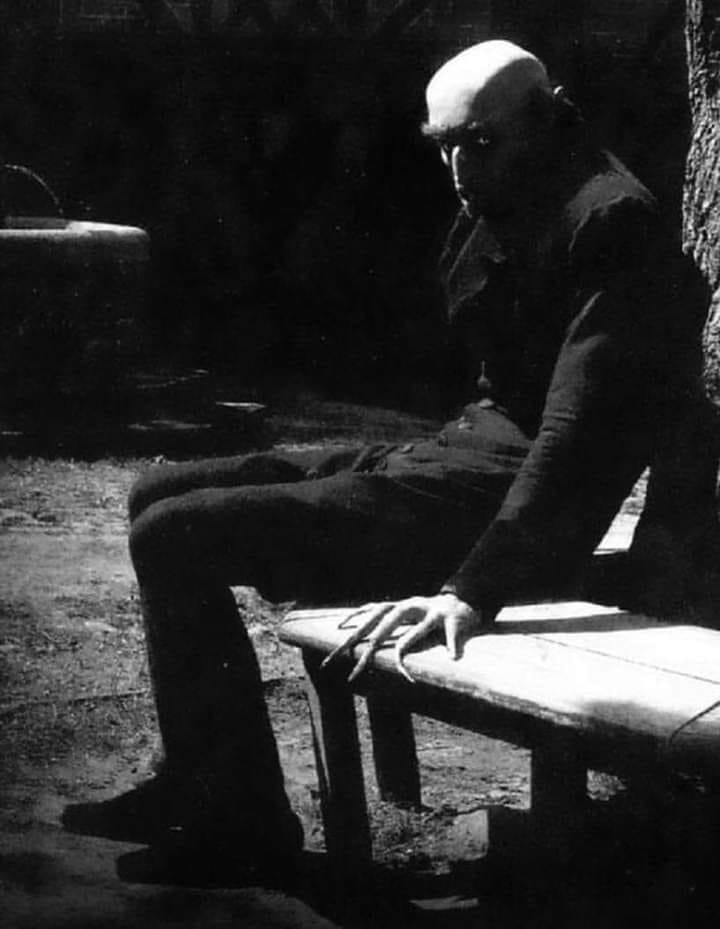

But a watershed phenomenon in the late 1920s and early 30s put America over the top in cinema’s unofficial horror-movie arms race: A steady stream of German directors, actors, and film techs began arriving in Hollywood. Most of these émigrés were veterans of the German Expressionist film movement. This movement had produced enduring horror classics like Nosferatu, movies that continue to enthrall audiences—and which are still being re-made by directors—to this day. The dark visions of German Expressionism helped usher in Universal’s pre-Code horror heyday (1929-1934) and the film noir movement that followed.

Though this Substack is named after German Expressionism’s 1919 poetic Bible, Twilight of Humanity (“Menschheitsdämmerung”), we’ve said from the get-go we might occasionally stray a bit off course to explore topics related to the Expressionist movement more broadly. This is one of those times.

As you’ll see, both German Expressionist poetry and film functioned as close-knit branches of the same overall artistic movement. Its two modes of expression were tightly intertwined.

Expressionist poet Walter Hasenclever, whose poems appeared in Twilight of Humanity, wrote, “Of all the art forms of our time, cinema is the strongest, because it’s the most contemporary. Space and time in cinema serve to hypnotize the viewers.”

German director Paul Wegener, whose early horror films reflected the gloomy impact of Expressionist art, proclaimed in 1916, “The real poet of the movie must be the camera itself.” And Expressionist poet Walter Hasenclever, whose poems appeared in this newsletter’s namesake, Twilight of Humanity, opined, “Of all the art forms of our time, cinema is the strongest, because it’s the most contemporary. Space and time in cinema serve to hypnotize the viewers.” Lotte Eisner summed it up when she wrote in The Haunted Screen: German Expressionism in the Cinema, that Germany in the 1910s evinced an “attraction towards all that is obscure and undetermined, towards the kind of brooding speculative reflection called Grübelei which culminated in the apocalyptic doctrine of Expressionism.”

In 2009, Roger Ebert wrote:

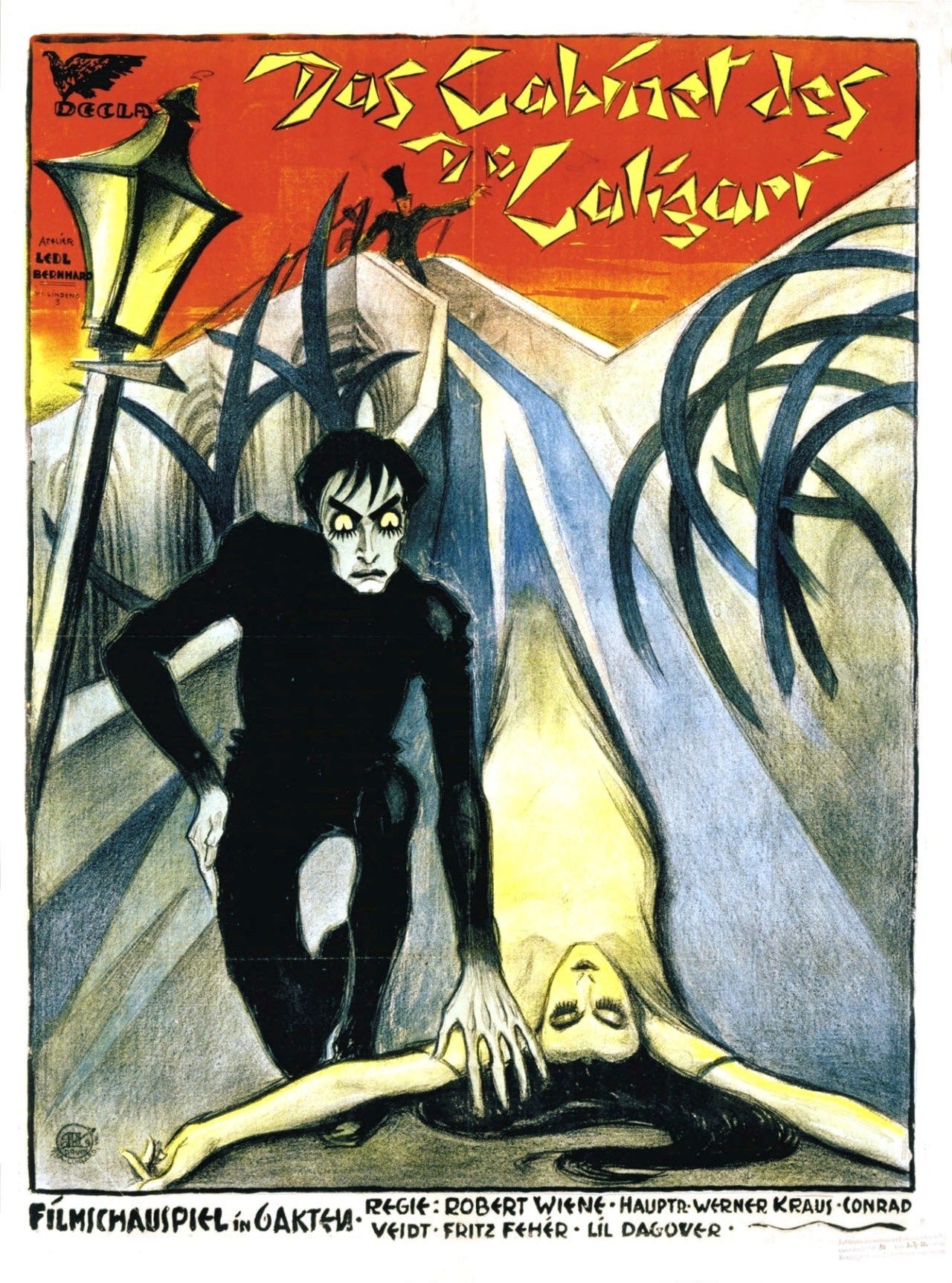

A case can be made that The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari was the first true horror film. There had been earlier ghost stories and the eerie serial "Fantomas" made in 1913-14, but their characters were inhabiting a recognizable world. "Caligari" creates a mindscape, a subjective psychological fantasy. In this world, unspeakable horror becomes possible.

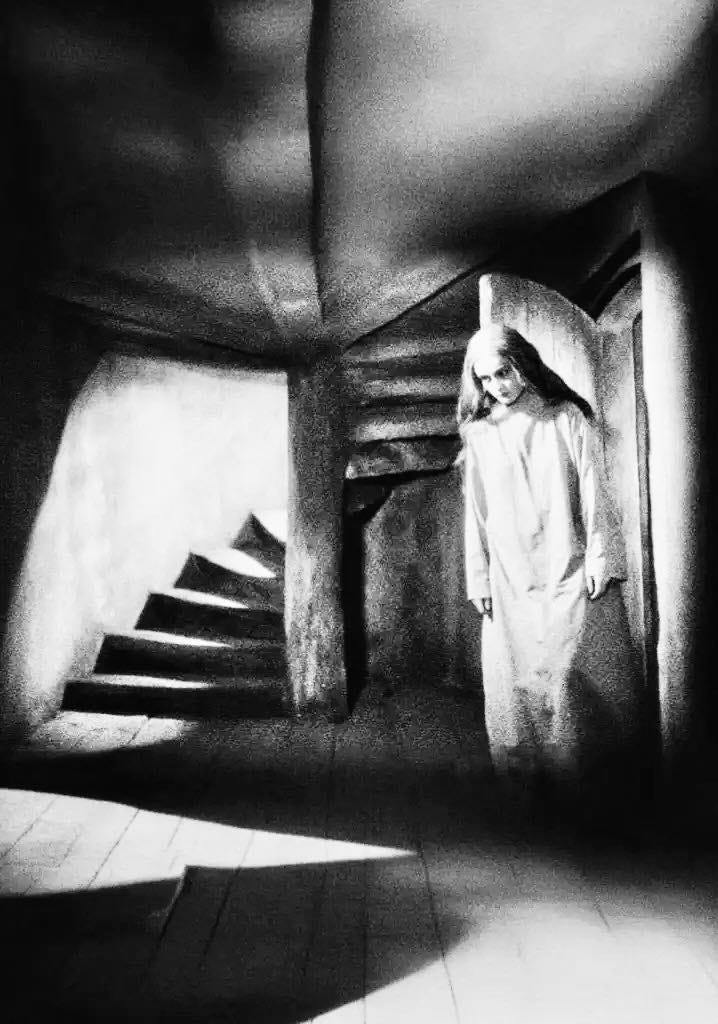

Of course, Caligari was a product of the filmmaking wing of the same German Expressionist art movement that produced the nightmarish renderings of Ludwig Meidner and Otto Dix as well as the apocalyptic poetry of Twilight of Humanity. Directed by Robert Wiene, Caligari memorably featured the nightmarishly skewed sets of artist Walter Reimann, member of a key 1910s Expressionist art group associated with avant-garde magazine Der Sturm. Caligari starred Conrad Veidt, Werner Krauss, and Lil Dagover, all mainstays of both silent Expressionist and horror films—there wasn’t often much difference between the two—in 1910s/20s Germany.

Ebert’s qualifier that “a case could be made” that Caligari was the first “true” horror movie is well taken; Ebert knew as well as anyone else that debates about the “first horror film” grind on to this day. Nowadays, George Méliès is usually accorded this honor, even if the films of Méliès average less than eight minutes apiece. Méliès’ 1896 House of the Devil (“Le Manoir du diable”), for example, is often considered to be the first horror film even though it clocks in at a mere 3 minutes. (What constitutes the first feature-length horror film is a different issue altogether, and we’ll address it later.)

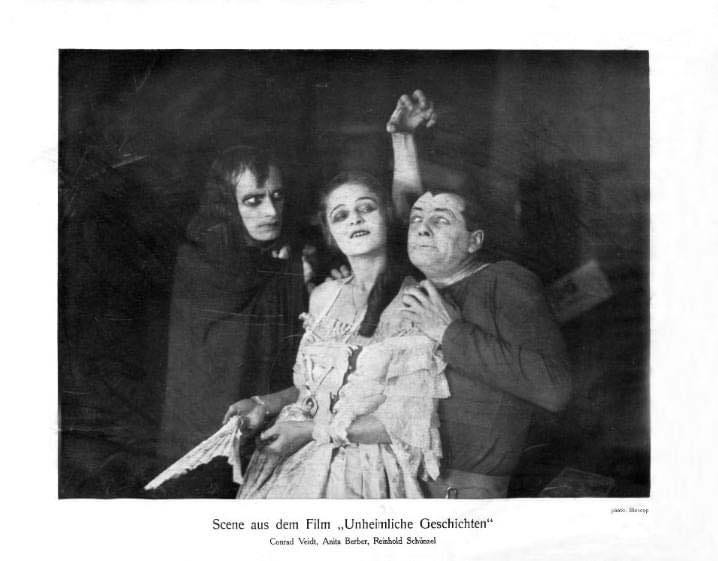

About 16 years after Méliès’ House of the Devil, Germany made its first entry into feature-length horror with Stellan Rye and Hans Heinz Ewers’ The Student of Prague (“Der Student von Prag”). The movie starred Paul Wegener, an actor who’d soon become a one-man powerhouse in German horror directing and acting in his own right. The Student of Prague was, in fact, based on elements of Edgar Allan Poe’s short story “William Wilson,” not the first time the shadow of Poe would loom large over early horror—and especially Expressionist—cinema. In 1919, for example, Eerie Tales (“Unheimliche Geschichten”)—possibly the world’s first horror anthology film—would see Conrad Veidt and avant-garde cabaret dancer Anita Berber co-starring in a movie that presented another Poe adaptation in the Expressionist film milieu.

As we’re reaching the maximum length allowed for emails here, this topic will be continued in Part 2 of this post.

This is Twilight of Humanity: German Expressionist Poetry in English.