Alfred Wolfenstein: Can you think of a name more German? (Well, perhaps if his first name had been Dieter, or Johann…)

Although I associate the Wolfenstein name with id Software’s 1990sWolfenstein 3D first-person shooter video game—yeah, that’s how old I am—the poet Alfred Wolfenstein was a peacenik and sensitive soul who appeared in print for the first time about 80 years before the violent-for-its-time computer game came out. Wolfenstein-the-poet’s first collection of verse, Godless Years, appeared in 1914, thanks mainly to the patronage of another important German-language writer I haven’t discussed yet in this Substack: Rainer Maria Rilke.

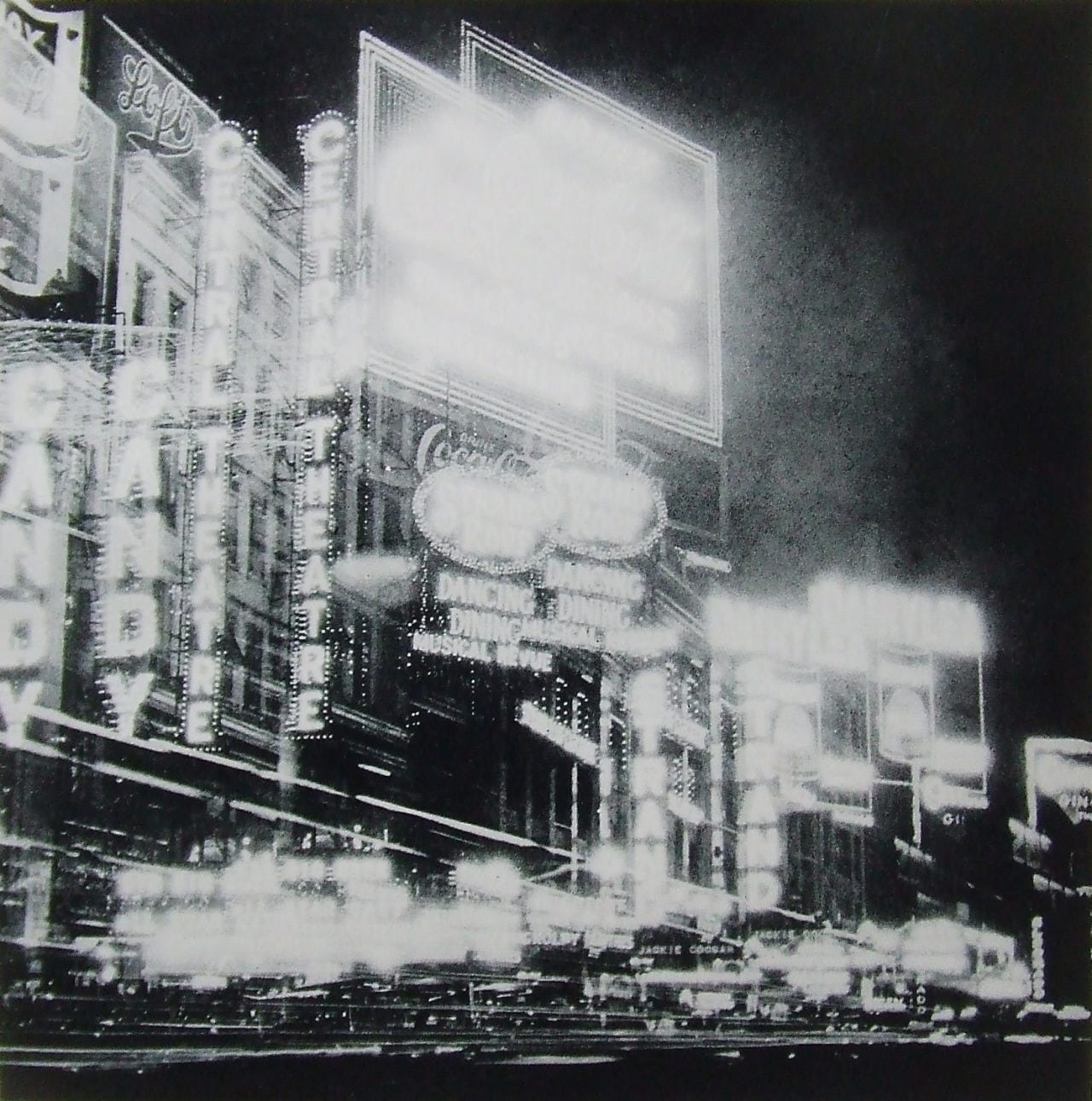

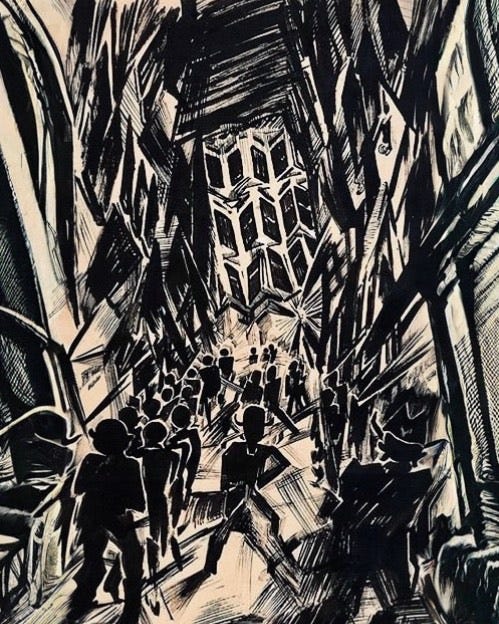

But as crucial a writer as many feel Rilke is, we must put him back aside for now. He does not appear in the 1919 Twilight of Humanity anthology of Expressionist literature after which this Substack is named. Thirteen of Alfred Wolfenstein’s poems, however, do. Below is the first poem of Wolfenstein’s to appear in Twilight of Humanity, “City Dwellers” (“Stadter”), a fourteen-line quatorzain or irregular sonnet first published in 1914. It portrays the alienation of city life and the misery of urban overcrowding that was the thematic focus of so much writing and art in the early Modern era.

Like much of his cohort in the Expressionist scene, Wolfenstein lived a colorful but ultimately tragic life. He survived World War I only to find himself—like pretty much all of his fellow writers and artists—blacklisted by the Nazis in the early 1930s. He was a producer, they said, of “degenerate” art.

As the 1930s progressed, Wolfenstein increasingly feared for his life if he stayed in Germany, not just for his politically-tinged plays (which had enjoyed some success in the 1920s in the Weimar Republic), but for other reasons. As far as Germany’s new fascist government was concerned, the writer had several marks against him: 1) He was a member of the pacifist German League for Human Rights (“Deutsche Liga für Menschenrechte”), an antiwar organization banned by the Third Reich from 1933 until 1945; 2) He was an avowed communist who had participated in the short-lived, revolutionary Bavarian Soviet Republic (or Munich Soviet Republic) with fellow playwright Ernst Toller in 1918; and 3) He was Jewish.

So Wolfenstein fled to Prague, Czechoslovakia, in 1933, after Hitler came to power. When the Germans marched to take the Sudetenland from Czechoslovakia in 1938, he relocated to France. He ultimately tried to leave France as well—with the help of his former patron, Rainer Maria Rilke—but he acted too late: He spent much of World War II hiding out in Nazi-occupied Paris under an assumed name, Albert Worlin.

Hounding him the whole time was a chronic heart condition that had exempted him from service in the First World War, but which only worsened as he aged. He turned 57 when the Nazis captured Paris in 1940. Unable to endure his degenerating condition any longer, Wolfenstein decided to risk his life and checked himself into a hospital in occupied Paris in 1944. There, it was not cardiac disease that claimed him—at least not wholly. Depression did. Alfred Wolfenstein committed suicide at age 62, in 1945, in the hospital he’d admitted himself into.

Wolfenstein’s poem below, “The City Dwellers (“Stadter”) exhibits characteristics of a sonnet, albeit with some deviations. It consists of fourteen lines with a discernible rhyme scheme (ABAB CDCD EFEF GG) in the original German. However, it does not adhere strictly to the traditional sonnet forms (Italian or English) in terms of meter. This loose interpretation of the sonnet form might reflect the sense of fragmentation and disruption associated with modern urban life, and again, I feel most comfortable calling it a quatorzain, as I did with Wilhelm Klemm’s poem “My Time” (“Meine Zeit”), which I made a post about earlier.

THE CITY DWELLERS (1914)

by Alfred Wolfenstein

Windows perforate walls of houses, spaced

closely together as holes in a sieve. And the

houses themselves are all thrown together,

strangling the streets into swollen grey corpses.

Crammed into the trams, several rows deep,

People are also all bunched together, interlaced.

Their narrow gazes refuse to look to each side.

Desires jab restlessly into other desires.

The walls at my home are as thin-skinned as

people; in my apartment, when I weep

at night, all the neighbors can hear me.

A whisper’s like a shout there, but it’s like I live

in a remote cave. Weeping is ignored, neglected,

unacknowledged; each of us remains: alone.

This is Twilight of Humanity: German Expressionist Poetry in English.

The original German version of Alfred Wolfenstein’s 1914 poem “Stadter” is below:

STADTER

Alfred Wolfenstein

Nah wie Löcher eines Siebes stehn

Fenster beieinander, drängend fassen

Häuser sich so dicht an, daß die Straßen

Grau geschwollen wie Gewürgte sehn.

Ineinander dicht hineingehakt

Sitzen in den Trams die zwei Fassaden

Leute, wo die Blicke eng ausladen

Und Begierde ineinander ragt.

Unsre Wände sind so dünn wie Haut,

Dass ein jeder teilnimmt, wenn ich weine,

Flüstern dringt hinüber wie Gegröhle:

Und wie stumm in abgeschloßner Höhle

Unberührt und ungeschaut

Steht doch jeder fern und fühlt: alleine.

All content above, unless otherwise indicated (viz.. Wolfenstein’s poem) is copyright © 2024 Oliver Sheppard.