Brigitte Helm, Germany's Second Lady of Expressionist Horror

A Brief Look at a Career Cut Short

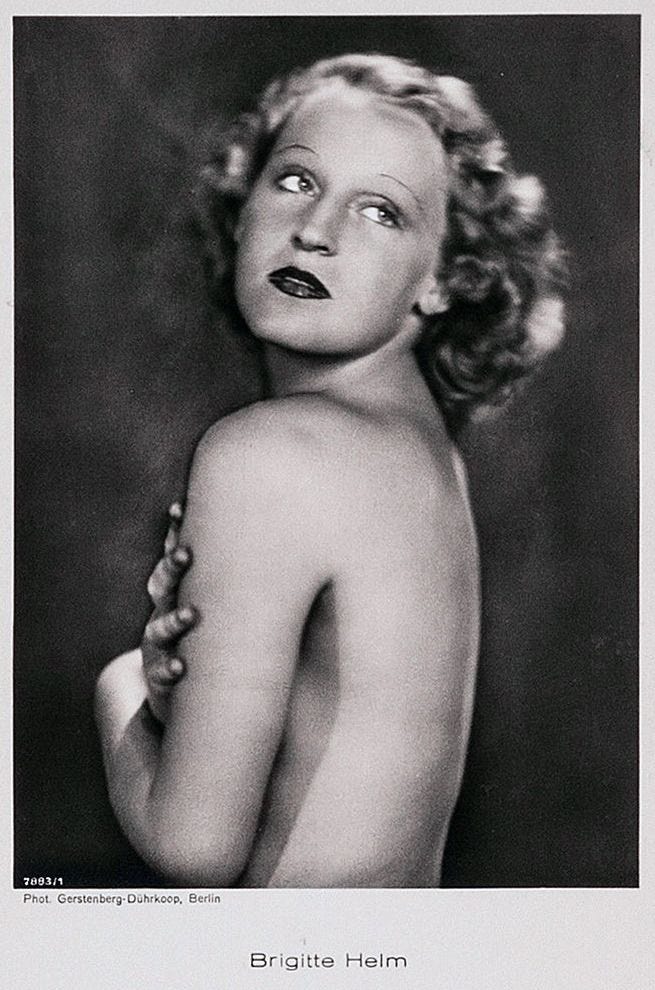

In 1996, when it was announced that German actress Brigitte Helm, aged 88, had passed away from heart failure, many evinced surprise that she was still alive. Where had the platinum-blonde star of Frtiz Lang’s Metropolis and G.W. Pabst’s L’Atlantide been hiding all these years?

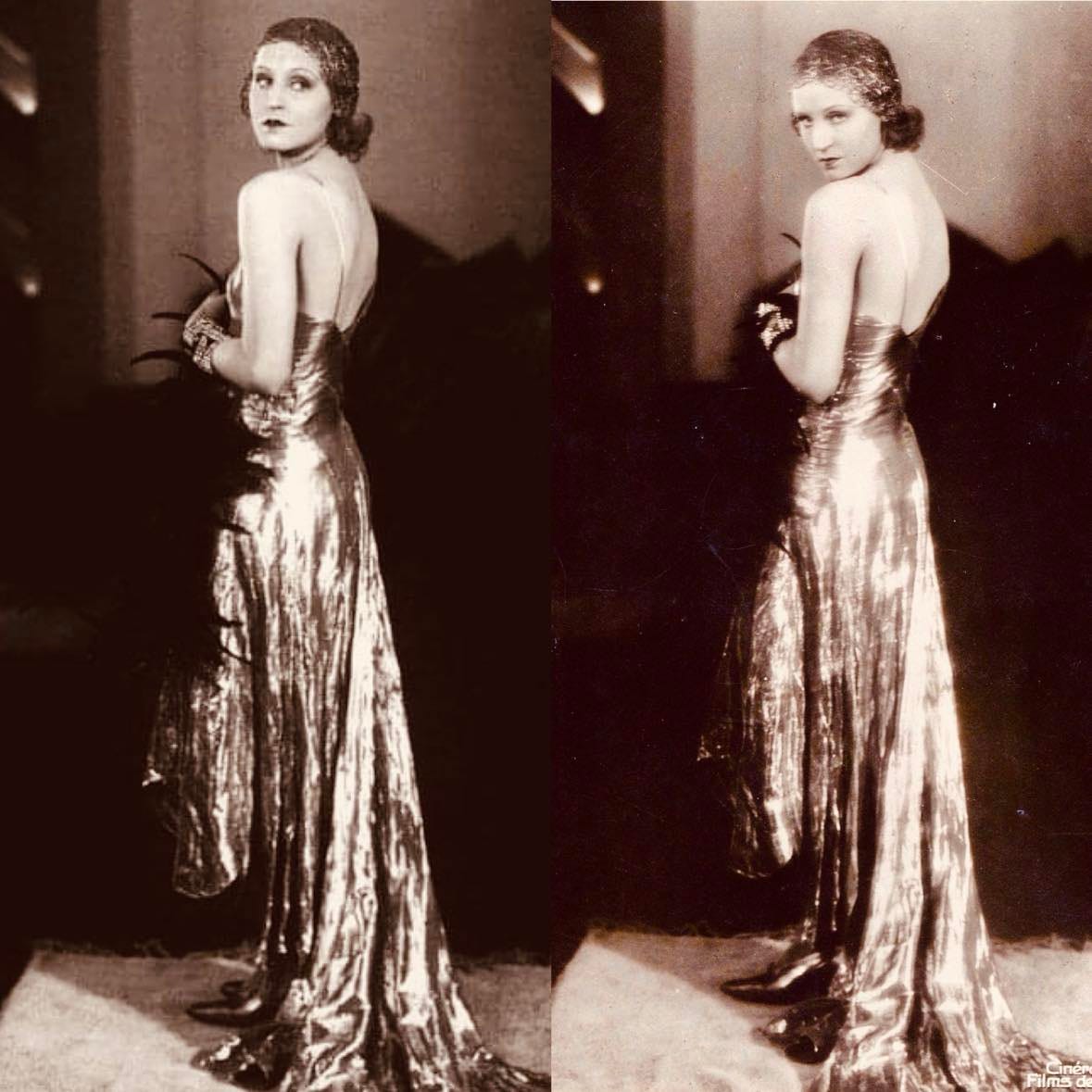

Like Greta Garbo—an actress with whom Brigitte was sometimes unfavorably compared (much to her chagrin)—the star of Metropolis had been passing the years far from the limelight. (In the small resort town of Ascona in southern Switzerland, to be exact.) Indeed, Brigitte Helm stayed successfully out of public view for over six decades—from 1935 until her death in 1996—by her own choice.

Helm left her film career abruptly. Her sudden exit in 1935 unintentionally helped solidify her status as one of the quintessential faces of Weimar cinema—perhaps as the quintessential face—though preserving her legacy in such a way had nothing to do with her reasons for quitting.

The Weimar Republic had itself left the world’s stage around, roughly, the same time that Brigitte Helm departed. She quit her film career less than two years after the Weimar Republic fell, as soon as her contract with UFA expired. Her film career’s conclusion at such a coincidentally auspicious time has tied her all the more securely to Weimar’s historical career; she seems forever that era’s avatar. That she was only 27 when she retired from movies ensures the public only knows the youthful Brigitte—the sleek, the radiant, and the beautiful Brigitte, frozen fast into her youth onto silver nitrate filmstock forever.

Brigitte Helm “was regarded as such a perfect embodiment of the era's ideal of cool sophistication,” wrote Robert Mcg. Thomas, Jr in his 1996 obituary for Brigitte Helm in The New York Times, “that when she turned Josef von Sternberg down for the starring role in Blue Angel, he had to settle for Marlene Dietrich.”

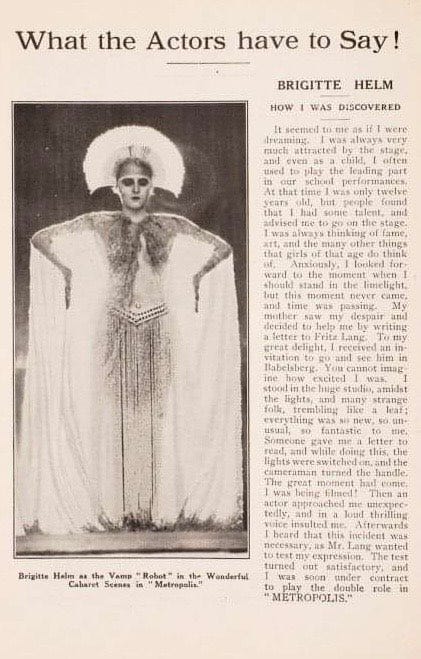

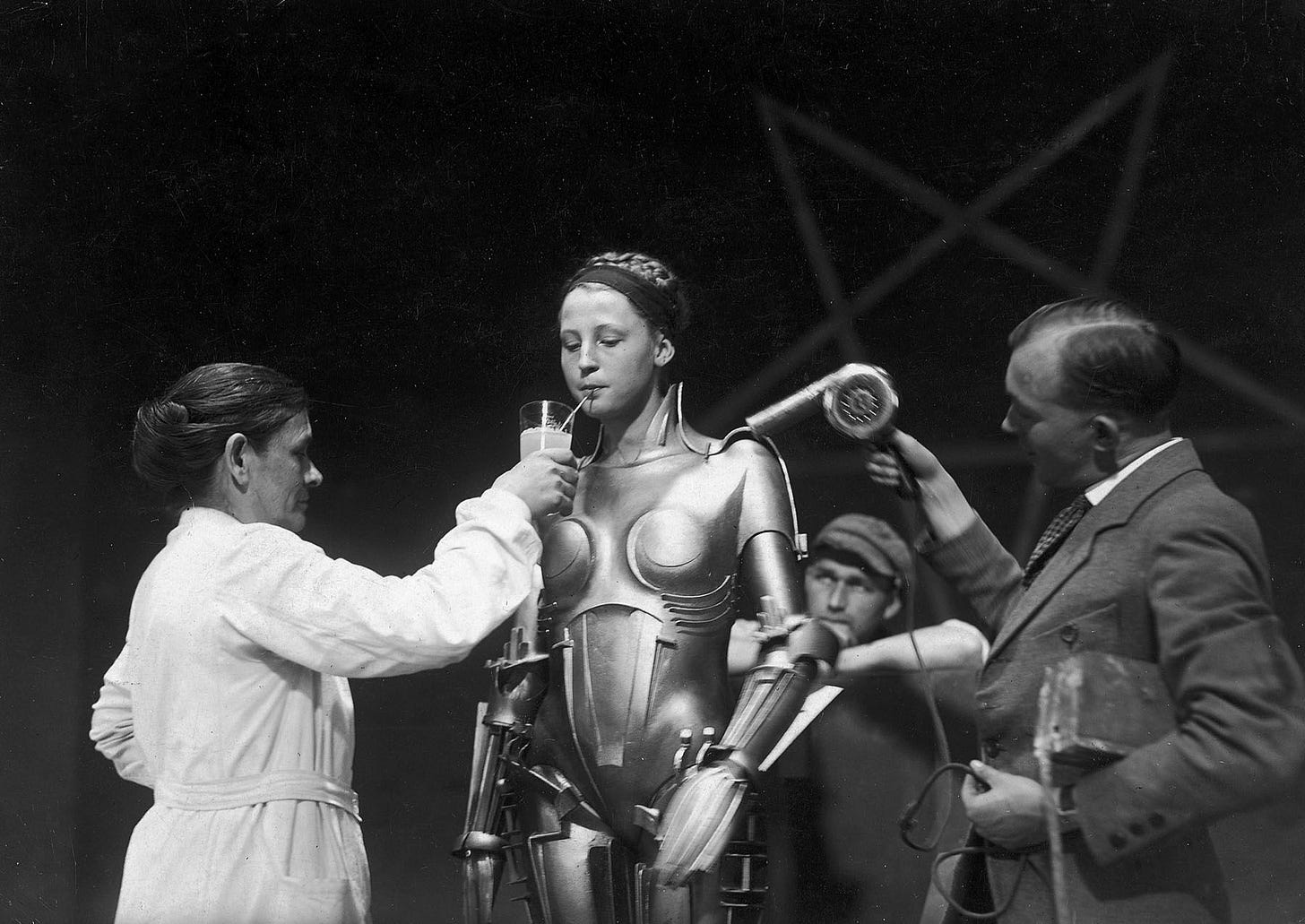

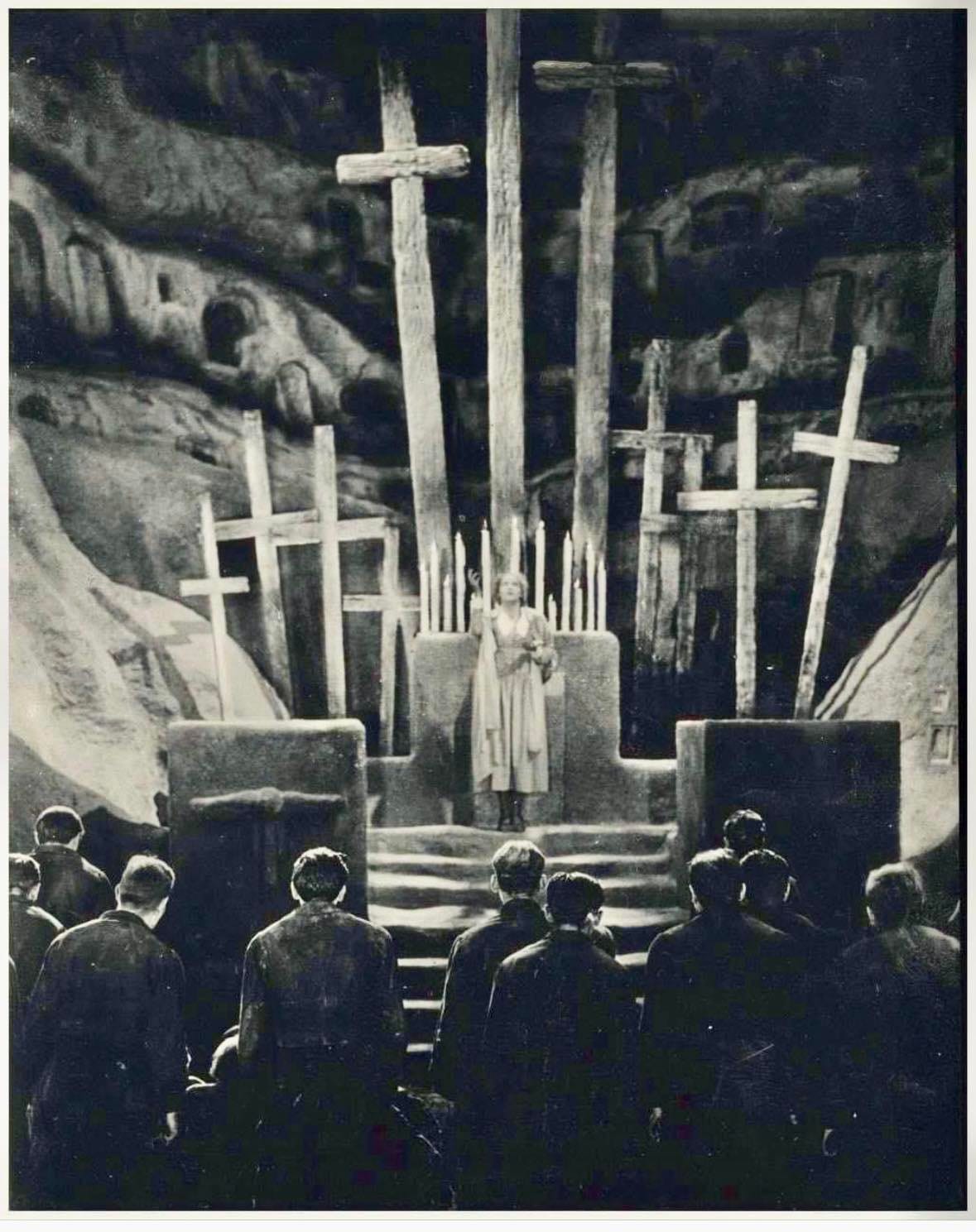

Or, as film historian Werner Sudendorff writes at The Independent: “Her mimicry and gestures were much affected by Expressionism: as the saintly Maria [in Metropolis] she makes wide eyes, clasps her hands to her breast and puckers up her mouth for a chaste kiss. As Maria [sic; actually, the robot is named Futura—ed.] the robot she is only a sexual body and object of desire, the personification of sin, a ‘witch’ of lust and an erotic mad image of the night.”

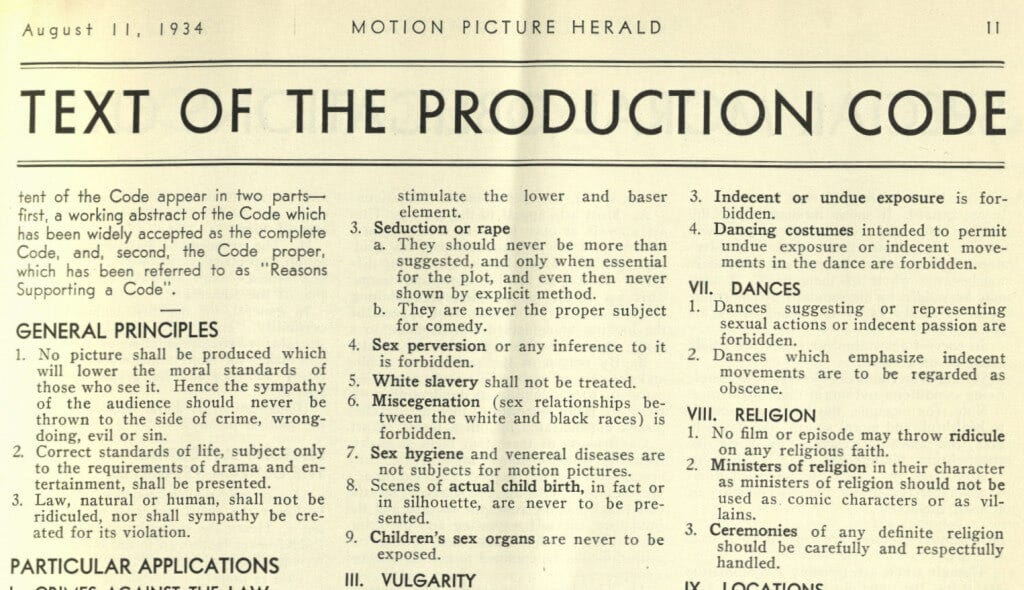

In the early and mid-1930s, political and cultural forces were conspiring to dramatically change the character of the arts in the West. None were transformed so dramatically then as cinema. In the United States in 1935—the year Brigitte Helm chose to retire—the censorious Hays Motion Picture Production Code began its first full year of enforcement, bringing to an end the relatively freewheeling—if not often downright libertinous—period of Hollywood filmmaking now referred to as “the pre-Code era.” Similar repressive forces were afoot in Brigitte’s native Germany, but these forces operated on a much larger, and much more terrifying, scale.

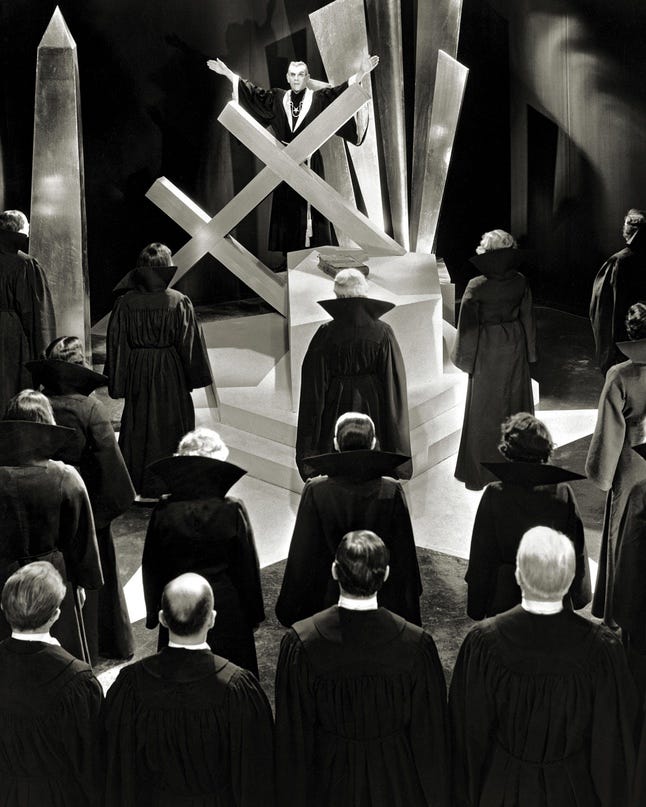

Ownership of German moviemaking powerhouse UFA was placed into Nazi Party hands in 1933, shortly after Hitler came to power—UFA being, of course, where Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, starring Brigitte Helm, had been made only a few years before. Indeed, UFA had been the womb from which many Expressionist or Expressionist-influenced movies were born. Direct Nazi ownership of the studio ensured artistic freedom there came to an end.

The next year, in September of 1934, the Third Reich followed up its acquisition of UFA with its infamous entartete kunst, or degenerate art, proclamations. Pronouncing certain artistic styles as officially verboten not only demonstrated that control of the arts had passed firmly into the hands of the state, but other decrees from Hitler and his cabinet ministers had the effect of directly banning the German Expressionist movement specifically. Although some might claim Expressionism had died out by 1934 anyway, the Nazis resolved to single it out for persecution regardless.* (*Joseph Goebbels, who tried to entertain sophisticated aesthetic pretensions, apparently argued within the Nazi Party to save Expressionism from the chopping block. However, Goebbels’ arguments fell on mostly deaf ears, and he lost out to chief party ideologue Alfred Rosenberg, who despised Expressionism. Hitler sided with Rosenberg in the Autumn of 1934, and Expressionism was banned.)

Brigitte Helm made only a few more films after the Nazis’ entartete kunst proclamations. Out of 37 movie credits spanning a career that lasted from 1925 until 1935, only 4 or 5 of Helm’s movies were made after the Nazis instituted their September 1934 “degenerate art” bans. Her last movies under the Nazis assumed a dull and propagandistic character: One of her last films, 1934’s Gold, is sometimes called “The Nazi Metropolis,” as it features Brigitte struggling against the wicked predations of a corrupt British millionaire who wants to synthetically create gold for himself. A movie featuring an avaricious Englishman as its villain was useful at a time when international tensions between Germany and England were quickly escalating. As CineSavant writes at Trailers From Hell, “The unspoken message [in Gold] is that a weakened Germany is being cheated in the world economy because it lacks the resources to exploit its superior technology... This ‘England plays dirty’ theme mirrors Germany’s bitterness toward England for at least the better part of a century of colonial, naval and financial competition. Versailles and WW1 aren’t mentioned in Gold, but that had to be on the minds of the audience as well: Germany innovates and works hard, but is consistently handed a raw deal [by the Allies].”

Of Gold, IMDB further notes: “The Casino Theatre on East 86th Street in New York City's German neighborhood, Yorkville, opened its doors with the American premiere of Gold and would become the flagship venue for the release of Nazi-produced … films during the mid to late 1930s in the United States.” It’s hard to imagine Brigitte Helm being satisfied with being relegated to roles in such films.

But for that matter, the forces of repression inside Germany had already been building to some form of a climax. By the late 1920s, when Metropolis was being filmed, many German filmmakers saw the writing on the wall and started what I’ve referred to elsewhere as the “brain drain” of moviemaking talent out of the Fatherland. (Most Expressionist talent went to America.) Norbert Wolf and Uta Grosenick provide just one example of Nazi repression of Expressionist art in their 2004 book Expressionism: “In 1930, Wilhelm Frick, a Nazi, became Minister for Culture and Education in the state of Thuringia. By his order, 70 mostly Expressionist paintings were removed from the permanent exhibition of the Weimar Schlossmuseum in 1930.”

And as I’ve also written elsewhere, several Expressionist writers’ lives ultimately ended in Nazi captivity. For example, Expressionist poet Jakob van Hoddis, who I wrote about on this Subnstack not all that long ago, died in Sobibor.

The exodus of Expressionist-linked cinematic figures like Paul Leni, Conrad Veidt, Fritz Lang, Karl Freund, and others rendered the German moviemaking scene artistically impoverished. Brigitte Helm was dealing with her own demons in the early 1930s, alcohol addiction among them—a familiar and unfortunate affliction common among movie stars both then and now, especially among those who, like Brigitte, have been quickly thrust into the most prominent ranks of fame and fortune. Still, Brigitte came to the same conclusion her colleagues-in-exile already had: Germany, especially its movie industry, was no longer a place for a serious artist to call home. As Pam Hutchinson writes at the excellent Silent London website:

”This was a time, according to German politician Gustav Stresemann, in which the people of Germany, intoxicated by the possibilities of the [post-WWI] world, were dancing on a volcano. Danger was afoot. In Metropolis, Helm’s crooked finger lured the hapless citizens to the brink. And audiences followed.”

Film historians offer different reasons for Brigitte Helm’s abrupt departure from the movies. The environment in Berlin was increasingly unhealthy, both psychologically and politically. For a sensitive artist already struggling with substance abuse issues, the added threat of political persecution was probably too much.

According to Robert Mcg. Thomas Jr., Brigitte Helm left Germany’s film industry in the 1930s because of the changes in the cultural and political environment mentioned above: “[I]n 1935, disgusted with the Nazi takeover of the film industry, [Brigitte Helm] abruptly quit, marrying an industrialist, Hugo von Kunheim, himself a Nazi opponent.” Helm had signed a ten-year contract with UFA in 1925. She left the movies and her birth country of Germany forever when her contract came up for renewal in 1935.

There’s no doubt that, had she wanted, Brigitte Helm could have negotiated a new contract and achieved perhaps even greater fame. Unlike so many of her fellow thespians, Helm had successfully transitioned from silent films to talkies. Audiences found her voice pleasing, and she worked well on the new audio-rich soundstages.

But her personal life was spiraling out of control—badly. As Brigitte’s drinking grew worse, she was involved in multiple traffic accidents, each one worse than the last. Finally, Helm was put in jail on a vehicular manslaughter charge—a crime referred to now in the United States as “intoxication manslaughter.” Specific details of Helm’s crash and what happened to her victim are murky, but according to Nazi Party Press Chief Obergruppenführer Otto Dietrich’s book, The Hitler I Knew, Adolf Hitler was informed of Helm’s situation and intervened personally to see that all charges against the beloved German film star were dropped. Helm was released from prison. She was badly shaken, but she was still alive.

There were rumors that Helm was Hitler’s favorite actress. Similar rumors exist to this day about Helm’s Expressionist colleague Lil Dagover, too. Whatever the case, Helm’s own reckless behavior—lethal this time—coupled with the subsequent receipt of unsolicited help from a man she viscerally despised—Nazi fuhrer Adolf Hitler himself—triggered a profound emotional crisis and something like a nervous breakdown. On the other side of her breakdown, Helm resolved to change her life radically. No more acting. No more movies. No more Germany. And she followed through.

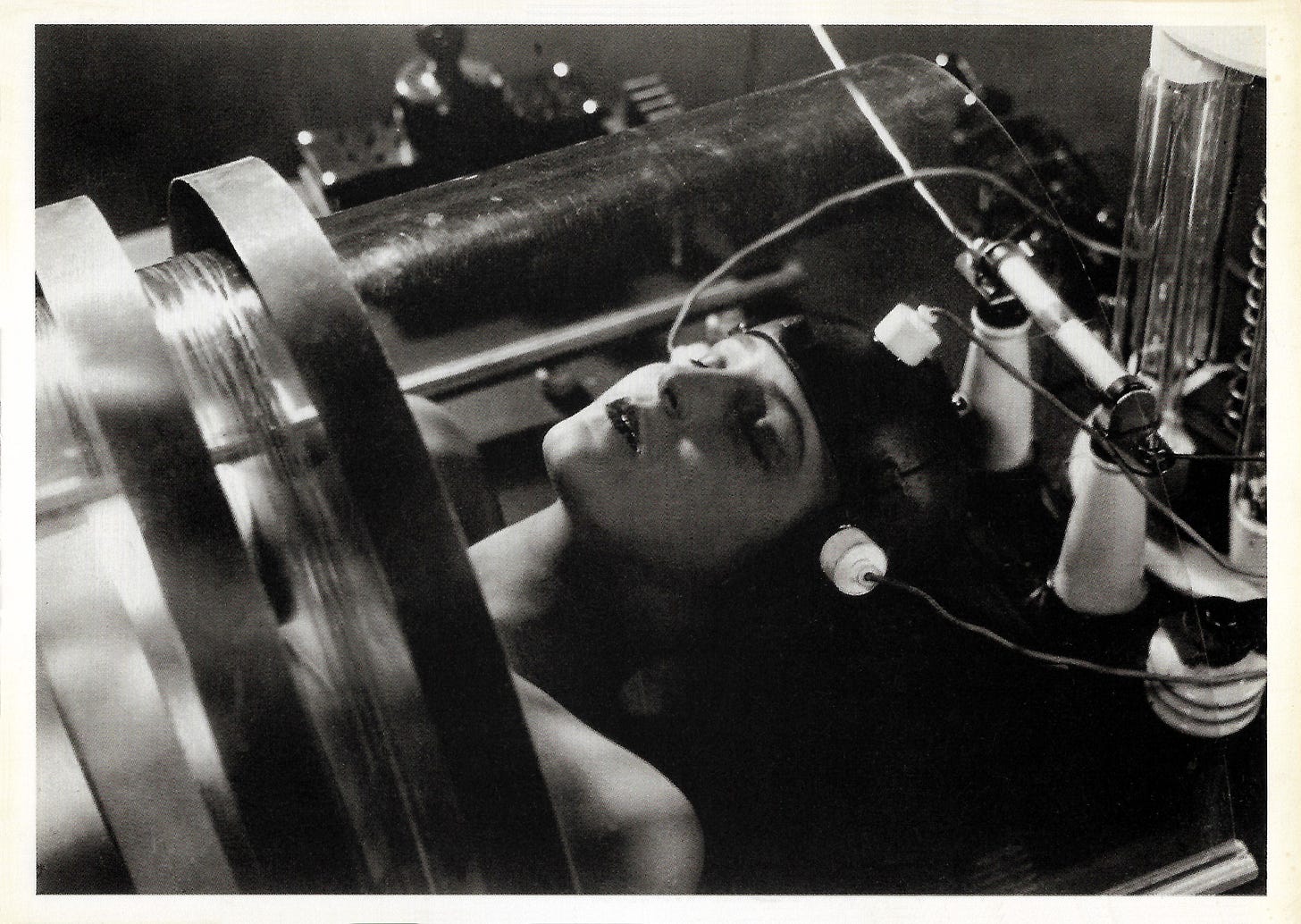

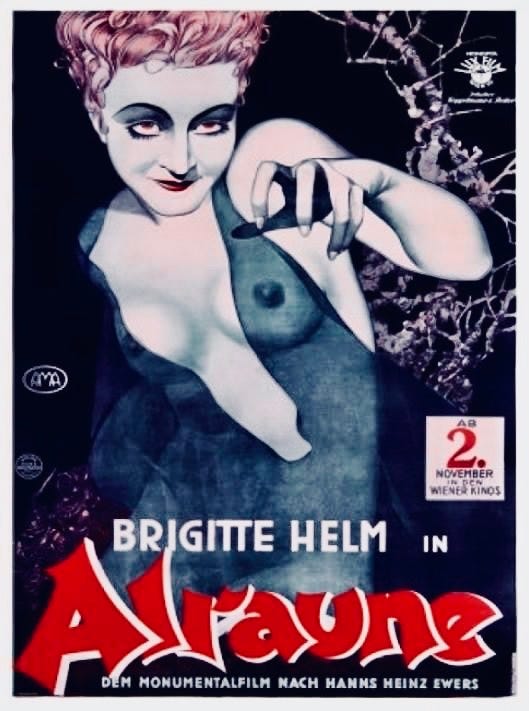

Helm's distinctive features, with their sharp angles and enigmatic gaze, proved an ideal canvas for the exaggerated expressions and stylized visuals that defined German Expressionism. This is strikingly evident in her portrayal of the character Alraune from Henrik Galeen's Alraune (1928), a silent horror film based on the homonymous Hanns Heinz Ewers novel from 1911.

This movie offered Helm a role that deviated significantly from the innocent Maria of Metropolis, allowing her to explore darker facets of the human psyche and the unsettling allure of the "femme fatale." As AFI astutely notes in its movie summary, 1928’s Alraune is “a precursor to [Yorgos Lanthimos’ 2023] POOR THINGS by nearly a century.” In Alraune, as in Poor Things, a crazed scientist creates, as an experiment, a conscience-less Frankensteinian woman driven by pure guile and lust. Also, as in 2023’s Poor Things, in 1928’s ALRAUNE the lab-created woman is adopted by her scientist-creator—in Alraune’s case, by Professor Jakob ten Brinken (played by always-excellent German Expressionist veteran Paul Wegener). In ALRAUNE, the creation process is perhaps even more shocking than that portrayed in Poor Things: In the 1920s German film, a sex worker is impregnated with the sperm of a hanged murderer. The child born of this scandalous insemination is Brigitte Helm’s soulless Alraune ten Brinken character. Vampire-like, she drains and despoils man after man, driven by unchecked id. In Sweden, the film was released as Vampyren; the film poster displayed a languorous and leggy likeness of Brigitte Helm wearing a short yellow skirt.

Helm navigates the film's exploration of artificiality, sexuality, and the monstrous feminine, embodying Alraune's tragic fate with a blend of innocence and chilling eroticism. The film and Helm's performance within it serve as a potent reflection of societal anxieties surrounding science, morality, and the burgeoning liberation of women in Weimar Germany.

In the 1928 silent version directed by Henrik Galeen, Helm relies on gesture and expression to convey Alraune's manipulative nature. Her eyes, wide and innocent, mask a calculating mind. A slight tilt of her head, a delicate touch, become weapons of seduction, drawing men to their doom. The film's expressionistic visuals, with their distorted sets and stark contrasts, amplify Helm's performance, creating a world where shadows and secrets reign supreme.

The 1930 sound version of Alraune, directed by Expressionist horror veteran Richard Oswald (who directed 1919’s Unheimliche Geschichten, one of the first horror anthologies in film history), allows Helm to expand her portrayal. Her voice, soft and seductive, adds another layer to Alraune's manipulative charm. She delivers lines with a chilling detachment, revealing the character's lack of empathy and her cold-hearted pursuit of pleasure. The addition of sound enhances the film's unsettling atmosphere, with eerie music and sound effects underscoring Alraune's destructive power.

Helm's performance in both films transcends the typical vamp archetype. Her Alraune is not simply a villain; she is a tragic figure, a victim of her own unnatural origins. Helm subtly conveys the character's inner turmoil, hinting at a longing for connection that is forever out of reach. This nuanced portrayal elevates the films beyond mere horror, exploring themes of identity, free will, and the dark side of human desire.

As a contemporary German critic wrote of Brigitte Helm’s performance in the first, silent version of Alraune:

Helm, that creature of the night with eyes like pools of liquid obsidian! Here, she embodies the very essence of perverse allure. As Alraune, the woman sprouted from a mandrake root fertilized with the seed of a hanged man, she is Galeen’s embodiment of forbidden fruit. Her beauty is a venomous bloom, intoxicating and deadly. Observe the way she moves, a sinuous predator stalking her prey. Lions roar when she is near. Her lips, painted a crimson that screams of passion and bloodshed, curl into a smile that promises untold delights and untold dangers. In her gaze, one glimpses the abyss, a swirling vortex of primal urges and untamed desires. […] But Helm's performance is not merely a physical display. There is a subtle undercurrent of melancholy that runs through her portrayal of Alraune. She is a creature born into a world that does not understand her, a world that fears her power and seeks to control it. In her eyes, one sees a yearning for connection, a longing for love that can never be truly fulfilled.

Helm's career coincided with the transition to sound film, a challenge many silent stars failed to overcome. Yet, she successfully navigated this shift, starring in movies like Gloria (1931) and The Blue Danube (1932), proving her talent extended beyond the expressive power of silent acting. The walls were closing in nonetheless, however, both in her struggle against addiction and in the increasingly stifling artistic and political environment fostered by the Nazis. Helm found a fortunate escape from all this—and she even found personal redemption—in marriage and motherhood, becoming a mother to four children after she departed from her film career and relocated with her husband to the picturesque and peaceful Swiss lakeside town of Ancona. She preferred to forget her time in the movies and the imploding nightmare of Germany of the late 1920s and early 1930s, and her ill-treatment by an auteur regarded by the rest of the world as a genius (Fritz Lang). According to The Independent, during the six decades of her estrangement from film, Brigitte Helm “never appeared on the stage or on television, refused all invitations and didn't give a single interview.”

(Note: In the title, I mention that Helm is Germany’s “Second Lady” of Expressionist horror. Perhaps you’re wondering who the “First Lady” is. That would and will forever be Lil Dagover.)