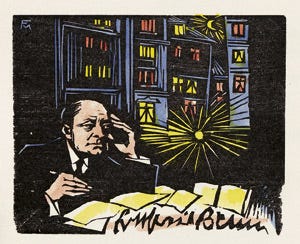

Gottfried Benn, Pathologist of Modernity

Against Sentimentality, Against Romanticism | Poem No. 15/278

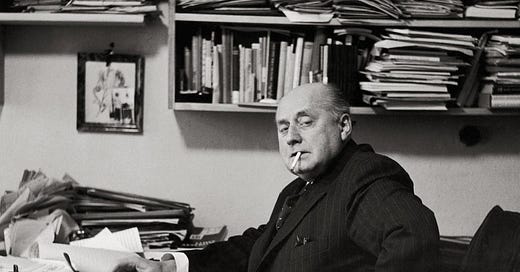

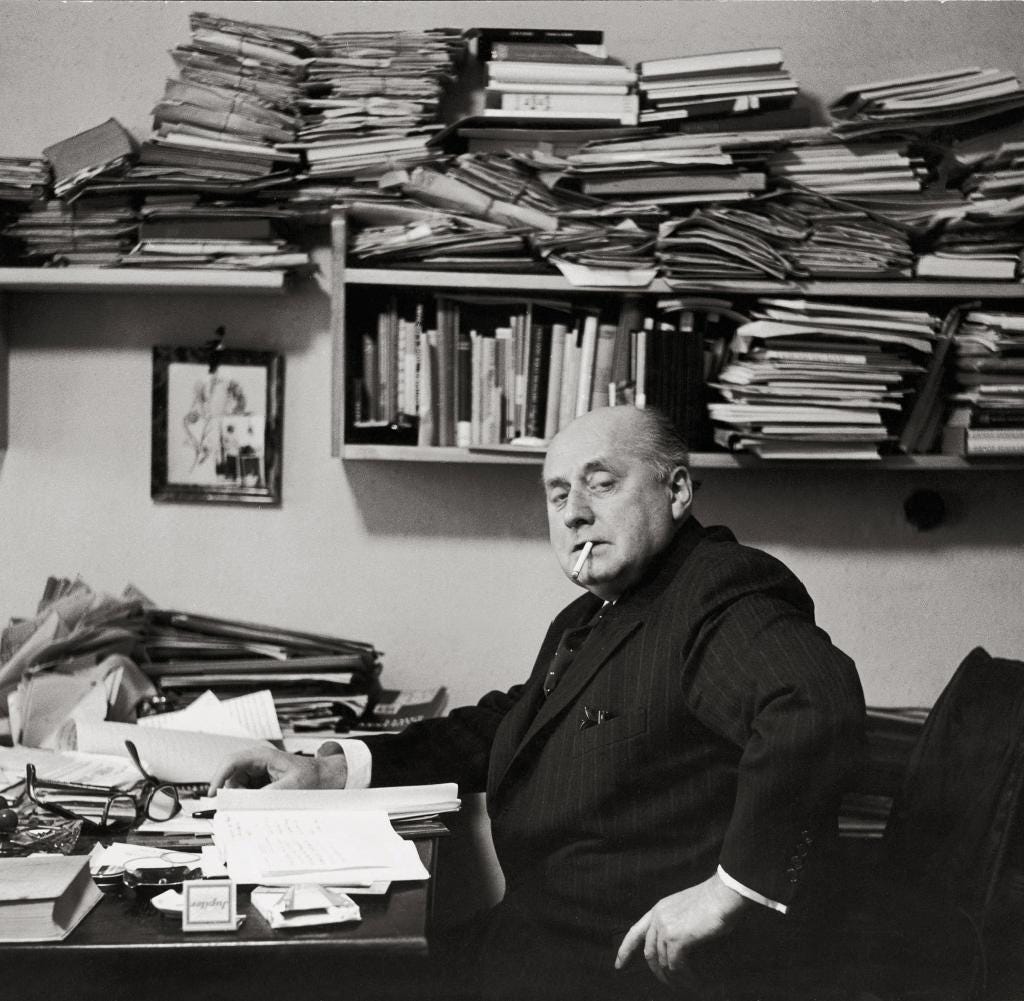

In the autopsy room of modernism, few have wielded the writer’s scalpel with the precision of German poet Gottfried Benn (1886-1956)—five-time Nobel Prize nominee, Georg Büchner Prize winner, and perhaps the most medically accurate nihilist German literature has produced.

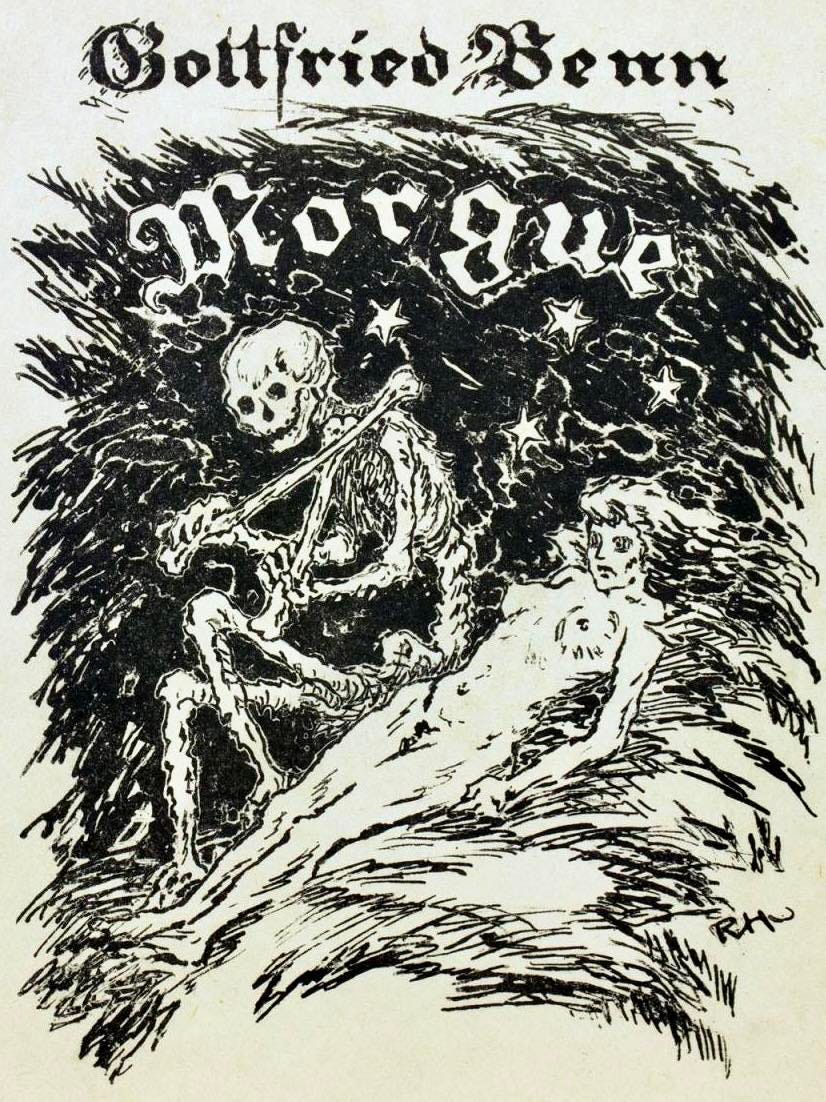

Benn debuted his early writing during the German Expressionist period. Most notably, this includes his (in)famous 1912 chapbook “Morgue and Other Poems,” a thin work containing only 13 poems but which sent shockwaves throughout the German literary establishment at the time. Benn was 26 and a practicing physician. Benn wrote of his state of mind:

I had originally been a psychiatrist, an assistant in an insane asylum, until at the age of 26 I began to notice an unusual phenomenon, which became more and more critical—in short, I was no longer able to muster any interest in an individual case. […] I delved into descriptions of that condition known as alienation or depersonalization of the sphere of perception. I began to recognize that the ego was a structure that was striving with a force, next to which gravity is like the pull of a snowflake, for a condition in which nothing that modern culture calls an intellectual faculty is important, but where everything civilization, led by academic psychiatry, had made disrespectable and labelled neurasthenia … admitted the deep, limitless, mythically ancient alienation between the ego and the world.

Many of Benn’s “Morgue” poems later appeared in the 1919 Twilight of Humanity anthology of Expressionist verse after which this Substack is named, and which also featured the other best poets of that era: Georg Trakl, Georg Heym, Jakob van Hoddis, and Benn’s sometime-lover, the Jewish poet Else Lasker-Schüler.

Benn’s thirteen groundbreaking “Morgue” poems were inspired both by the 1906 “Morgue” of Rainer Maria Rilke and the 1910 “Morgue” of Expressionist forefather Georg Heym. Indeed, Heym had also written a short story, “The Autopsy,” or “Dissection” (in English translation), from the point of view of a corpse undergoing an autopsy, a story that exerted an influence on Benn’s early clinical poems that shared similar themes of autopsies and death, and evinced what now might be called “body horror.” Unlike Rilke and Heym, however, Benn had actual experience performing autopsies, with actual corpses. The old writerly advice of “write what you know” is precisely what Benn did: Throughout his unsentimental and coldly ironic “Morgue” poems, he detailed personal experience with cutting open cadavers, touring cancer wards, and the like.

Although Benn’s relation to the Expressionist movement was sometimes ambiguous, ultimately he was proud of his association with it, especially later in life. He even provided some of the most useful accounts of the movement as well as some of the best definitions of the definition-averse term “German Expressionism,” as in his retrospective 1955 essay “The Lyrical Poetry of the Expressionist Decade,” written when he was 69, a year before his death:

”Expressionism was a revolt with eruptions, ecstasies, hate, longing for a new humanity, with the dashing of language in order to dash the world... They [the Expressionist poets] condensed, filtered, experimented so that with this expressive method they could lift themselves, their spirit, the disintegrated, tortured, deranged existence of their decades up into those spheres of form in which, over sunken metropolises and decayed imperiums, the artist, he alone, consecrates his epoch and his people to human immortality... But there it is still, 1910-1920. My generation. Hammering the absolute into abstract, hard forms: image, verse, flute song... It was an incriminated generation: ridiculed, jeered, cast out politically as degenerate—a generation precipitous, sparkling, surging, affected by calamities and wars, marked for a short life... In other words, Expressionism and the Expressionist decade: ...It rose up, fought its battles on all the Catalaunian fields, and declined. Raised its flag over Bastille, Kremlin, Golgotha—only Olympus it could not reach, nor any other classical terrain.”

(from Gottfried Benn’s Lyrik des expressionistischen Jahrzehnts, 1955)

To read Benn is tantamount to witnessing consciousness perform surgery upon itself: the poet-physician's lines cut through sentimentality with the same swift efficiency he employed when dissecting dead bodies during his medical career. Benn's inaugural collection (“Morgue and Other Poems”) detonated like a literary grenade in pre-war Germany. “Morgue” is one of those so-simple-it’s-genius kinds of literary works—brief poems that read like the cold-blooded autopsy notes from the most Stoic of forensic pathologists.

Consider the collection’s opening salvo—"Little Aster":

A drowned beer-driver was propped up on the slab.

Someone had stuck a lavender aster

between his teeth.

As I made the incision up from the chest

with a long knife

under the skin

to cut out the tongue and palate,

I must have nudged it, for it slid

into the brain lying adjacent.

I packed it into his chest cavity

with the excelsior

and then they sewed him up.

Drink your fill in your vase!

Rest easy,

little aster!

This is not mere épater la bourgeoisie—it's something more fundamental: the recognition that beauty and horror cohabit the same corporeal vessel. Benn refuses allegory; his flower is emphatically not a symbol. It is matter confronting matter in the theater of (rotting) flesh.

After his Expressionist phase, Benn developed what he termed "statische Gedichte" (static poems), a poetics of crystallization that attempted to arrest chaotic modernity into formal perfection. His intellectual trajectory—which included a brief, catastrophic flirtation with National Socialism before his mid- and late 1930s retreat into what he called "aristocratic nihilism"—reflects the contradictions of German intellectual life between the wars.

His five Nobel Prize nominations (1949, 1950, 1951, 1952, and 1953) came during his late renaissance, following the years of what he called his “inner emigration,” essentially a form of mentally (and spiritually) checking out while outwardly doing what he thought he had to do to legally get by. The Swedish Academy's reluctance to award him the Nobel likely stemmed from his political compromises in the 1930s and 1940s. However, by the early 1950s he had written some of his most potent philosophical reflections: "Double Life" and "Problems of Lyric Poetry."

Eight of Benn’s poems appear in the original 1919 edition of Kurt Pinthus’ Twilight of Humanity anthology. But one of the most interesting poems in that volume is not by Benn, but about him—a fawning poem titled “Doctor Benn” penned by his sometime-lover, the Jewish poet Else Lasker-Schüler, one of the great female poets associated with Expressionism (as well as one of its few good erotic poets). “All my flowers I would pour into your blood,” she wrote.

I’ll write more about Benn’s poetry in the future and delve there and then into the thorny subject of his political dalliances, which have impeded appreciation of his work in our era, an era in which an estimation of a writer’s politics is considered integral to rendering any verdict on their literary talent. Suffice it to say that, unlike the majority of Expressionists, who were radically left-wing, Benn was politically moderate-to-conservative in the 1910s and 1920s—though like many who are politically conservative he was, in his personal life, quite liberal (drug use, multiple affairs and marriages, support for avant-garde art, etc.). Certainly, Benn’s graphic poetry shocked middle-class sensibilities. In 1933 he began a year of supporting Nazism, but by the late 1930s he found himself in the odd position of belonging to the Nazi Party while his poetry was deemed "degenerate art" (entartete kunst) by that same party’s edicts. In 1938, Benn was expelled from the Reichsschrifttumskammer (Reich Chamber of Literature), owing to his Expressionist work. This effectively ended his literary career until World War II was over. 40 years after its publication, editor Kurt Pinthus wrote, in a retrospective of the Twilight of Humanity anthology in which Benn appeared:

GOTTFRIED BENN, a Nazi supporter in the beginning, was very soon attacked in the most brutal way by them, and had himself and his work proscribed in 1936. He never recovered from this “double life,” not even in the last years of his fame.

Pinthus was resolutely left-wing, but unlike many critics today, he possessed a keen ability to appreciate a writer’s literary talent regardless of their political leanings (and Benn’s views were, indeed, never completely static throughout his life). Of course, Benn disavowed and wrote against fascism after the war ended, and by his own account privately felt revulsion toward National Socialism after the Night of the Long Knives shocked him out of his naïveté about the movement in July 1934 until he could publicly write against fascism after May 1945.

* * * * *

Benn’s poetry—especially his earlier poetry—sought to forcefully move literature from its lingering, residual Romanticism and away from romanticization. This was something not always achieved by other Expressionist writers; for all the lip service many Expressionists paid to breaking away from old traditions, there was still in much of Expressionism a tendency to cling to 19th-century notions of the Gothic and the pathos/emotionality prized by Romantic authors. With Benn, one finds an actual, clean break from such stuff.

So, what characterizes Benn-ian poetics? I would submit the following five aspects are paramount:

Anatomical precision/medical lexicon → used to destabilize middle-class/status quo sensibilities

Nihilistic materialism ↔ yearning for transcendence (the quintessential Expressionist paradox)

Fragmentary syntax performing the disintegration it describes

Atonality—rejection of harmonious cadences in favor of jagged rhythms

Wortkonstellationen—word constellations that create semantic ruptures

The two poems below illustrate this.

Before A Cornfield (1913)

by Gottfried Benn

Before a cornfield someone said:

The faithfulness and fairy-tale beauty of the cornflower

may be a good subject for painting by elegant ladies,

but I prefer the deep alto, the profundity, of the poppy.

It reminds me of pools of blood, of menstruation,

of hardship, of the last gasping of breath before death,

of starvation, of extinction—

in short: of the dark path of man.

Requiem (1912)

by Gottfried Benn

Two on each slab, men and women

crosswise. Crowded, naked, but without pain.

The head up. The torso split open. The bodies

give birth for the last time.

Each fills three basins: from brain to testes.

And God's temple and the devil's lair

are now side by side in a bucket of slop,

sneering at Golgotha and man's fall.

The remainder are in coffins. Real newborns:

a man's legs, a child's torso, a woman's hair.

And I saw two who used to prostitute themselves,

lying there as though both were from the same womb.

—from “Morgue And Other Poems,” 1912

This is Twilight of Humanity: German Expressionist Poetry in English.

All words and translation(s) above are Copyright © 2025 Oliver Sheppard, unless otherwise noted.