Expressionist writer and critic Ernst Blass wrote that in his recollections of the early days of the Expressionist movement, a foremost thought was of “the possessed, fascinating, apodictic poet Jakob van Hoddis who was slowly afflicted by a serious psychosis.”

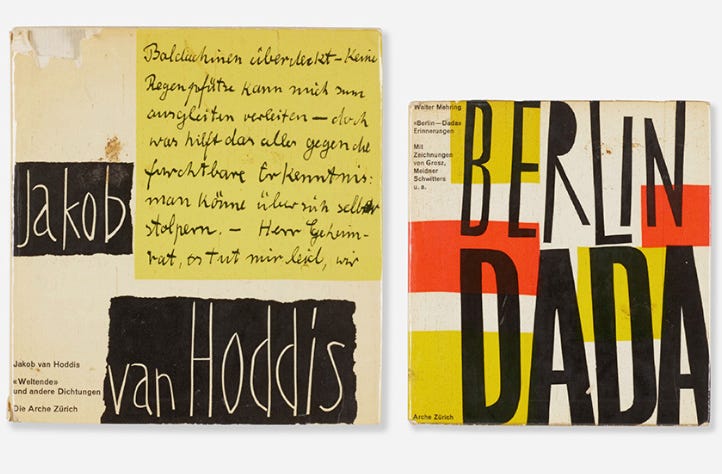

Van Hoddis is, along with the poet Georg Heym, one of the founders of literary German Expressionism, and indeed he was diagnosed with schizophrenia years after he initially burst on the German literary scene in 1911. Unlike Georg Heym, Van Hoddis is considered to be a figure seminal to Dadaist and Surrealist literature (Hoddis appeared in Tristan Tzara’s Dada #3 in 1918), too.

After learning that van Hoddis had met a tragic end in the Nazi concentration camp of Sobibor in 1942 at age 55, no less a figure than André Breton, the co-founder and ideological leader of the Surrealists, wrote this touching poetic tribute to him, incorporating elements from van Hoddis’ poem “Weltende” (“End of the World”) that I posted about some time back as the first poem that editor Kurt Pinthus chose to include in the 1919 Twilight of Humanity anthology:

A weather vane sings in the Berlin sky, an enchanted pump laughs beneath country ice, and a little book of poems won’t burn. It refuses to suffer the fate of so many other works for which Hitler’s dictatorship has arranged an auto-da-fé, in vain hopes of containing the revolutionary thought that is ever on the march. We are here at the extreme point of German poetry; van Hoddis’s voice reaches us from the highest and thinnest branch of the lightning-struck tree. The man, who leans a moment on Arp’s arm, stands out by his discordant behaviour: invited to dinner, he vigorously strikes his plate with his spoon in order to make a noise, and could easily be imagined, like Harpo Marx, offering his leg to the ladies. At the historical turning-point of the war’s end, as it is most cruelly experienced in Germany, he disappears into an insane asylum. Beautiful songs of the asylum, which celebrate the feeling of total freedom – military and other assemblies shatter against the walls. We are with them in the very country of black humour, recognizable by its symbolic, mysterious, invariable aspect: swarms of white flies, carpets of flowers, green-tinted cats.

(For a more complete biographical sketch of van Hoddis, see my post about him and his 1911 poem “End of the World,” which is here.)

Fellow poet Johannes R. Becher, another German Expressionist—who would become one of the cultural leaders of East Germany after World War II—and who I’ve also posted about here—provides the following sketch of his friend:

Ludwig Meidner has sketched [Jakob van Hoddis], attractive and animated as he scarcely imagined himself in normal life. He was dwarflike, of bedraggled appearance, grey, unshaven, pimply — unspeakable hands — at all times he was wrapped in a woolly scarf which desperately needed washing, shy, quite whimsical and already a little mad and soon afterwards he did end up in an asylum in Thuringia.

Indeed, the Art Institute of Chicago possesses Meidner’s sketch of the foundational poet, with this note: “Perhaps the most influential of the Expressionist literati, van Hoddis is often credited with writing the first truly Expressionist poem, his Weltende (End of the World), which consummates the apocalyptic hopes and fears of his generation.”

Five poems from Jakob van Hoddis appear in Twilight of Humanity, underscoring his importance to the volume and the Expressionist movement in general. “The City,” below, is the second of those five.

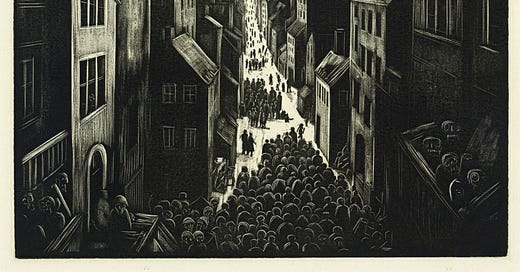

THE CITY

by Jakob Van Hoddis

I saw the moon and the cruel

Aegean Sea in all its multiform pomp.

In every path I’ve taken, I’ve grappled with the night.

Yet I’ve been escorted by seven bright torches

That glow through the clouds, ready for every victory.

"May I acquiesce to oblivion, may I be tortured

By the malevolent winds of great cities, of evil cities?

I’ve broken from the days of a desolate life!"

Forgotten journeys—your triumphs have

Long faded. I hear brilliant flutes now

And my own vain grieving in the sound of violins.

Translation copyright © 2024

Here’s Jakob van Hoddis’ “The City” as it appeared in its original German:

DIE STADT

by Jakob van Hoddis

Ich sah den Mond und des Ägaischen

Grausamen Meeres tausendfachen Pomp.

All meine Pfade rangen mit der Nacht.

Doch sieben Fackeln waren mein Geleit

Durch Wolken glühend,jedem Sieg bereit.

,,Darf ich dem Nichts erliegen,darf mich qualen

Der Stadte weiten Stadte böser Wind?

Da ich zerbrach den öden Tag des Lebens! "

Verschollene Fahrten! Eure Siege sind

Zu lange schon verflackt. Ah! helle Floten

Und Geigen tönen meinen Gram vergebens.

This is Twilight of Humanity: German Expressionist Poetry in English.

All content above, unless otherwise indicated, is copyright © 2024 Oliver Sheppard.