The Erotic Poetry of Else Lasker-Schüler

German Expressionism's Tawdry Romance | Poem No. 113 of 278

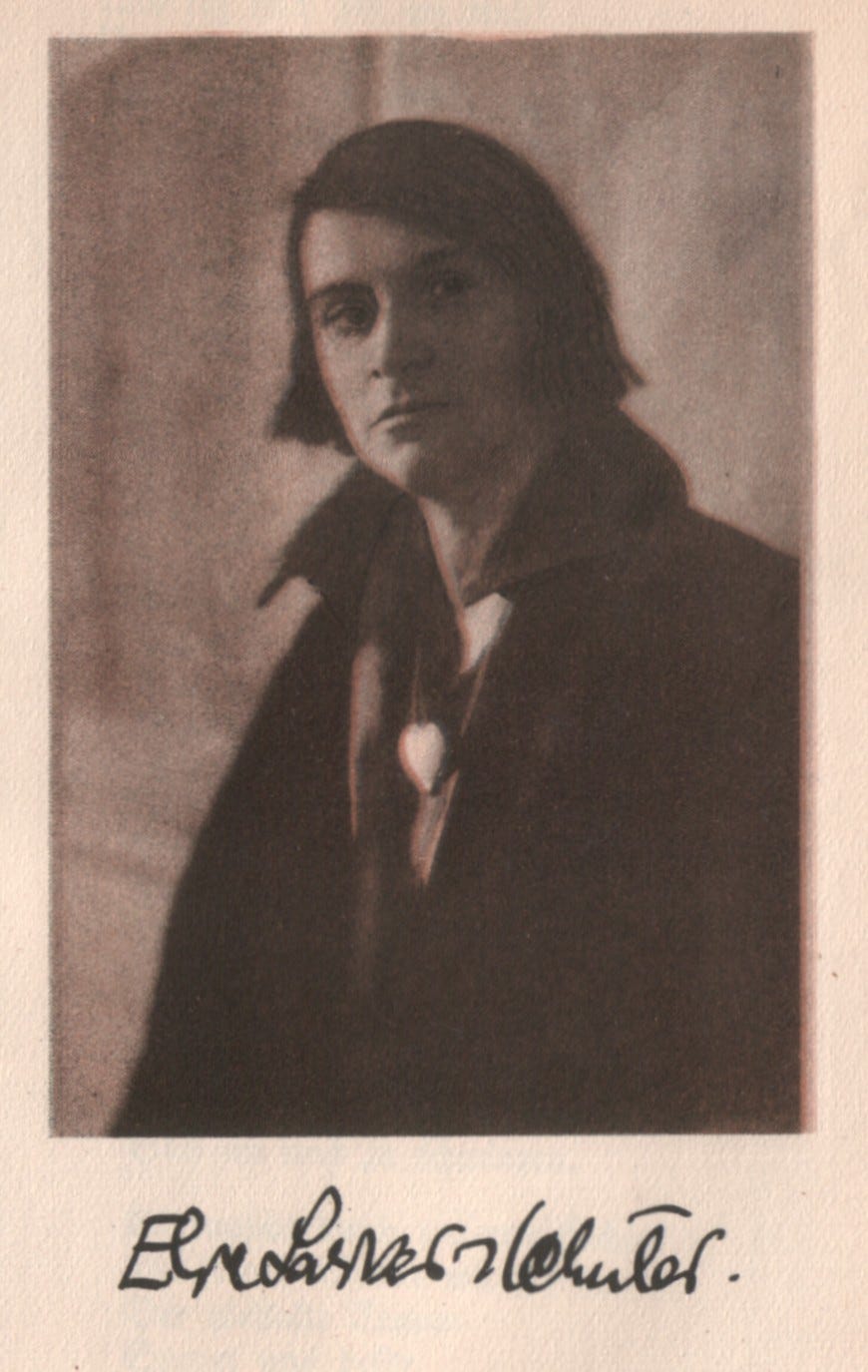

A few years after her 1945 death in Jerusalem, Gottfried Benn eulogized Else Lasker-Schüler as "the greatest poet Germany ever had." Franz Kafka, on the other hand, hated her: "I can't stand her poems,” Kafka wrote to his fiancée, Felice Bauer, in 1913. "I feel nothing but boredom with them."

Yet both Else Lasker-Schüler and Gottfried Benn appear in the seminal 1919 anthology of German Expressionist poetry, Twilight of Humanity, after which this Substack is named—and this includes one of the love poems Lasker-Schüler wrote to physician-poet Gottfried Benn that she had titled “Doctor Benn” (which is below).

The two poets’ affair was unusual in several ways: Lasker-Schüler was in her early 40s when she began sleeping with Benn; Benn was in his mid-20s and had achieved overnight success with his nine-poem "Morgue” chapbook. As well, Benn was raised strictly Protestant while Lasker-Schüler was Jewish (and quite the bohemian artiste of early 1900s German avant-garde circles).

In 1997, a movie was made in Germany, directed by overlooked female German filmmaker Helma Sanders-Brahm—about Else Lasker-Schüler and her romance with Gottfried Benn, who would go on to join the Nazi Party in 1933. The movie My Heart Is Mine Alone (“Mein Herz – niemandem!”) depicts the relationship between the two seminal German poets as a kind of Romeo and Juliette romance: “The story of the real-life love affair between Jewish poet Else Lasker-Schüler and Nazi poet Gottfried Benn is told largely through their poetry in this experimental drama,” a synopsis on the back of an American DVD of the movie reads.

Of course, calling Gottfried Benn “a Nazi poet” is a bit sensational, and doesn’t convey the full-breadth of the 5-time Nobel Prize nominee’s 5 decades of literary output. Benn did, indeed, spend a year actively supporting National Socialism in the early 1930s. By the late 1930s, however, he was expelled from the Reichsschrifttumskammer (the Reich Chamber of Literature), and his writing was banned in Germany. This owed to Benn’s Expressionist poetry, which the Nazis labeled “degenerate art” (entartete kunst). Though Benn was not put in personal danger, his literary career was effectively ended until World War II was over.

(As I wrote in a previous post, by mid-1934, Benn had already mentally checked out from the German politics of the day, according to his own writing. He began what he called “an inner emigration” away from the reality of the vile and unsolvable situation he realized he was in. Whether this seems a weak explanation (or “excuse”) is for readers to decide; Benn proceeded to remain in the Wehrmacht in the rank of major, though his physician status (and his age at this point) kept him far from the front lines of WWII. (Adam Thirlwell’s 2014 article in The New Republic covers Benn’s political “problematics” thoroughly enough.) Whatever the case, the fact that Benn championed the poetic works of his ex-lover, a Jewish poetess, as “the best Germany ever had,” speaks poignantly of his ultimate beliefs.)

As I’ve written elsewhere, Else Lasker-Schüler was not only one of the few good erotic poets associated with literary German Expressionism—which, for all the movement’s playing up of essence-over-appearance, rarely tackled anything explicitly erotic—she was also one of the few women associated with Expressionist literature. (Elsewhere, I’ve written about Gertrud Kolmar, a fellow-traveler and female poet of Expressionist significance, too.)

Indeed, Else Lasker-Schüler is essential not only to literary German Expressionism, but also to the European continent’s Modernist avant-garde period generally: Her first poetry collection, Styx, came out in 1902, and her friends and collaborators are a who’s who list of Modernist art and literature of the first half of the 20th-century: Her friends and compatriots include Georg Trakl, Franz Marc, Ernst Toller, George Grosz, Oskar Kokoschka, Martin Buber, Wassily Kandinsky, Chagall, and Karl Kraus, among many others. Her influence and literary activity from 1900 until her death in the 1940s is textbook Modernist literary avant-garde.

As Robert Rubsam writes at Poetry Foundation—

Many of the great artists of pre- and interwar Germany met Lasker-Schüler at the Café des Westens and featured in Walden’s epochal journal Der Sturm, including the painter Franz Marc, anarchist Johannes Holzmann, novelist Alfred Döblin, cabaretist Erich Mühsam, theorist Walter Benjamin, philosopher Martin Buber, and poets Georg Trakl and Gottfried Benn. Like the alternative groups of Lasker-Schüler’s early career, the Berlin avant-garde blended political and aesthetic radicalism, and provided a home for Jews and women excluded from Germany’s official artistic societies.

And yet it is the affair between Else and Gottfried Benn that continues to fascinate. As one German website puts it:

Else Lasker-Schuler and Gottfried Benn shocked their contemporaries over 100 years ago with their passionate and enthusiastic poetry (and their being together at all): Benn was a doctor and writer, with poems that came from the ‘morgue’ of his own experience, portrayed in his first book of poems, “Morgue.” Both poets had a short and intense love affair in 1912/13 that was reflected in their poems. While many literary scholars emphasize the difference between the two, Kerstin Decker makes the opposite case: ‘Like recognizes like.’ Both poets knew ‘the mental states where each ego ceases—a basic experience of togetherness .... and when the ego becomes reassembled, only to multiply infinitely.’ In their poems, Benn and Lasker-Schüler describe border states that are tense, deeply human, and yet also alien to everyday experience.

What follows are two of the poems titled “Doktor Benn” that Else Lasker-Schüler wrote about her lover, capped off by her poem “Love Song”:

Doctor Benn (I)

by Else Lasker-Schüler

He descends into the lowest vaults

of the hospital and dissects the dead—

an insatiable one who wants

to enrich himself with their secrets.

And he claims, ‘dead is dead.'

Yet he is pious in his unbelief;

he also loves houses of prayers,

dreaming altars, eyes that come

from afar: He is a Protestant heathen,

a Christian with an idol's head,

with a hawk's nose and a leopard

in his heart. (His heart is fur-spotted

and flayed open like an animal skin.)

He loves fur and he loves mead and

large stags roasted on a forest fire.

Once I said to him, “You are so completely

harsh, a rock, plain and rough—but you are

also the peace of the forest, of beechnuts

and red hawthorn and chestnuts in shade,

gold foliage, autumn leaves, the creek’s reeds.

And you are rooted in the earth, all hunting

and mountain-smoke and dandelions

and nettles and thunder.”

He stands unwaveringly, carrying the roof

of the world on his back. When I danced myself

to exhaustion and didn't know where to go,

I wanted to be soft and grey and lift up his arm

to bury myself beneath it, against him.

I feel like I’m a mosquito who teases

his face obnoxiously. But I’d like to be a

bee who could buzz around his stomach…

Long before I knew him, I was his reader;

his book of poems—Morgue—lay on my blanket:

Horrible art there, wonders of tragedy,

death reveries—all given form. Suffering tears

open the jaws of his words; those from churchyards

walk into hospital-wards and plant themselves

in front of sickbeds of exquisite pain.

Child-bearing women scream from delivery-rooms

to announce the end of the world.

Every line of his verse is a leopard's bite,

the pounce of a wild predator.

Human bone is his stylus.

With it, he opens up the word.

Doctor Benn (II)

by Else Lasker-Schüler

I always think about death.

Perhaps it’s that no one loves me.

I’ve wanted to be a silent image of a saint,

with everything inside me cleansed.

Dreamily colored evening red;

my eyes are cried sore.

I don't know where to go.

Like everywhere, to you.

You are my secret home.

I can’t imagine a house any quieter, anymore.

How I liked blooming sweetly

in the heaven-blue of your heart.

And I’ve tread so many soft paths

around your throbbing house, my home.

My Love Song

by Else Lasker-Schüler

My blood murmurs

like a secret spring,

always of you, always of me.

Beneath the reeling moon

dance my naked searching dreams,

sleepwalker children,

soft over dark hedgerows.

Oh, your lips are sun-kissed…

The intoxicating scent of your lips…

And out of bloom clusters silver-ringed

you smile… you, you.

Always the creeping trickling

over my skin

Out over my shoulder –

I listen in …

My blood murmurs

like a secret spring.

Else Lasker-Schüler (11 February 1869 – 22 January 1945) had 14 poems in the 1919 TWILIGHT OF HUMANITY anthology. It’s a credit to the foresight of editor Kurt Pinthus that he saw fit to include so many from her alongside Georg Trakl, Georg Heym, and Gottfried Benn.

Together with Richard Billinger, Else Lasker-Schüler received the coveted German literary Kleist Prize in 1932—the last awarded before the National Socialists seized power. On March 19, 1933, after physical attacks and fearing for her life as a Jewish woman in Germany, Lasker-Schüler emigrated to Zurich, Switzerland—but was subsequently banned from working there. In 1938, her German citizenship was revoked from afar, and so she became “without status,” or "schriftlos”—nation-less. In 1939, she traveled to Palestine and was prevented from returning to Switzerland by Swiss authorities because she lacked a visa (again, she had been rendered “nation-less”). She remained in Jerusalem, then, and in 1944 became seriously ill. After a heart attack, Else Lasker-Schuler died on January 22, 1945. She is buried on the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem.

This is Twilight of Humanity: German Expressionist Poetry in English.

All words and translation(s) above are Copyright © 2025 Oliver Sheppard, unless otherwise noted.