Gottfried Benn's "Morgue II" (1913)

Benn's hard-to-find sequel to 1912's MORGUE featured 5 new poetic vignettes | Here they are.

I’m not sure if the five poetic vignettes that comprise Gottfried Benn’s 1913 Morgue II cycle have ever been translated into English. (If so, I’ve never found them.) So I gave it a go myself. The results are at the bottom of this post.

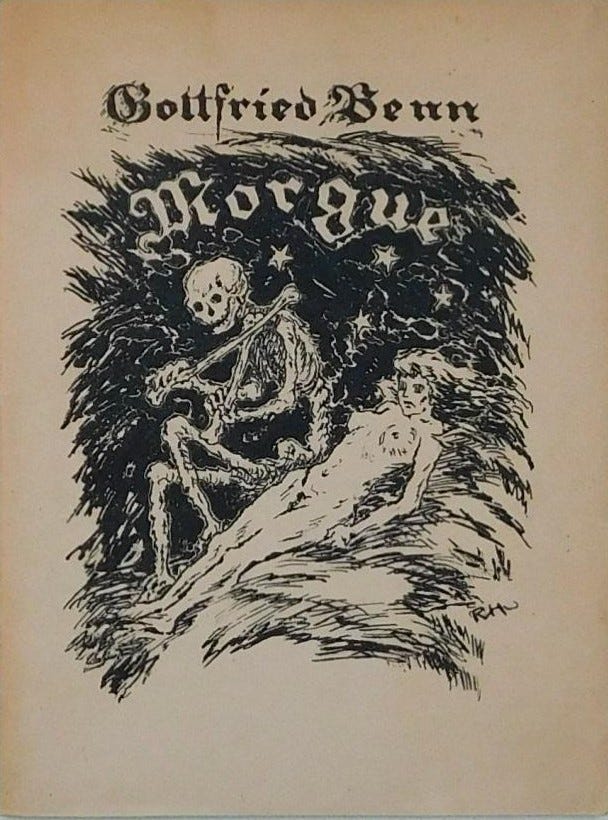

But first, some backstory about these five hard-to-find poems from Benn’s little-known sequel to his notorious 1912 Morgue and Other Poems chapbook.

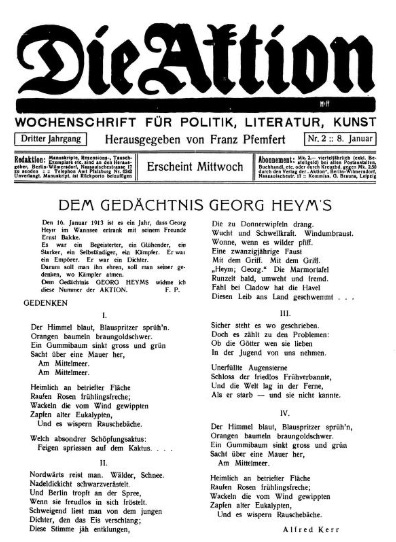

Thrilled as he was with the overnight success of his slim 1912 Morgue and Other Poems booklet (“Morgue und andere Gedichte”), and aware of his growing reputation as a shockingly cold and unsentimental writer—as a writer of brutally macabre verse, in fact—Benn happily accepted an invitation from editor Franz Pfamfert to publish more poems in the sardonic vein of Morgue for an upcoming issue of his magazine. This invitation came in late 1912, and the five resulting poems were published in a 1913 issue of Pfamfert’s Die Aktion. (I should note that some sources list the five published poetic vignettes as five sections of a single poem called “Morgue II.”) The issue was dedicated to the memory of Expressionist forebear Georg Heym, and in addition to Benn’s “Morgue II” 5-poem cycle, poems by Alfred Wolfenstein, Ernst Stadler, Jakob van Hoddis, and other Expressionist luminaries also appeared.

Benn seems to have decided to have a bit of fun with the five new “Morgue”-style poems. The “Morgue II” cycle has darkly humorous elements; several of its constituent poems have a wry, tongue-in-cheek character that plays upon the fast-growing notoriety of the explicit and gruesome nature of the original content of Morgue.

We also find that “Morgue II” is dedicated to Adolf Petrenz, the editor to whom Benn ultimately owed the success of Morgue—and in many ways to his whole subsequent writing career. Petrenz was editor of Berlin’s Taglichen Rundschau magazine, and it was to him that in early 1912 Benn had mailed the original manuscript containing the nine poems of Morgue. Though he could not use the poems, Petrenz recognized the value of Benn’s work and wanted to see it published soon—even if he could not do it himself. Petrenz immediately sent Benn’s manuscript over to colleague Alfred Richard Meyer, who ran a small, avant-garde literary press.

Upon reading the manuscript of the original Morgue poems, “I jumped out of my skin,” Meyer reminisced in his memoir. A poet himself, Meyer used his niche imprint to publish cutting-edge works by living German authors. (Indeed, the same issue of Die Aktion that features Benn’s “Morgue II” cycle also features a poem by Meyer.) Meyer was not just shocked by Benn’s verse; these coldly clinical poems were not the product of a drugged-out Bohemian—the kind of stuff to which Meyer was accustomed—but seemed to come from the pen of an actual, practicing medical professional. “Whoever had written these poems had done so out of medical experience and not out of some theory,” Meyer recalled. “The small volume [of Morgue and Other Poems] was set and printed in eight days, and it bore the date March 1912. Never before had the press in Germany responded to poetry in such an explosive, violent way.”

According to translator Simon Beattie (who in 2018 published his own fine edition of a five-poem version of Morgue in English): “The Expressionist verse of Morgue and Other Poems, inspired by Benn’s work as a pathologist, shocked readers at the time, but the first edition, printed in 500 copies, sold out within eight days.”

“What most disturbed Benn’s reviewers was the lack of emotive response that the poet showed towards the human detritus that was his subject matter,” notes Benn biographer Martin Travers in The Hour That Breaks, the only book-length biography of Gottfried Benn available in English. Travers notes that many reviewers evinced an oddly unsophisticated “lack of distinction between Benn and his persona” in their estimation of his work. That is, Benn’s verse struck commentators so harshly that it seemed to render them unable to distinguish between Benn, the actual person, and the narratorial voice and persona that was reflected in the poems of Morgue. Some reviewers intimated that a person who could write such stuff was probably, in all actuality, a cruel and sadistic monster.

Benn read these gasping reviews of Morgue with amusement. Despite some of the pearl-clutching among the general public, members of the Expressionist literati were enthused to have a new poet of such frank—and such frankly dramatic—power now in their ranks. This included veteran poet Else Lasker-Schüler, whose 1902 collection of poems, Styx, saw her anticipating the German Expressionist and Modernist literary movements, and from whom soon came several amatory poems dedicated to “Doctor Benn.” Lasker-Schüler and Benn indulged in a steamy love affair throughout 1912 and 1913 (the subject of the 1997 movie My Heart Is Mine Alone by Helma Sanders-Brahms). And both poets would appear in 1919’s omnibus Twilight of Humanity anthology of Expressionist verse, after which this Substack is named.

And so it was that Franz Pfamfert somehow convinced Benn to write “Morgue II” for his magazine, Die Aktion. Benn took the opportunity to poke some fun at readers’ expectations of his verse. They want morbid detachment? Here’s tasteless scatology. They want Gothic horror? How about sardonic absurdity? “Morgue II” appeared in Issue No. 2, Volume 3 of Die Aktion on January 8, 1913.

And lastly, one odd thing about “Morgue II”: It’s very hard to find any mention of this work anywhere in English-language materials about Gottfried Benn. For example, Benn biographer Martin Travers mentions the 5-poem cycle only once—and even then, only in passing—in his otherwise excellent 440+ page biography of Gottfried Benn, The Hour That Breaks: Gottfried Benn: A Biography (Peter Lang Press, 2015). “Benn consolidated his reputation through the publication of an entirely new cycle, Morgue II, which was published in January 1913 in a special supplement of the Die Aktion, dedicated to the memory of Georg Heym,” Travers notes in his book.

Here in English at last, then, are the five vignette-style poems that appeared as Morgue II in the January 8, 1913 issue of Die Aktion:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Twilight of Humanity: German Expressionist Poetry in English to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.